Pope Leo XIV’s 2025 visit to Turkey brought renewed global attention to the state of religious freedom in the country. His meetings with President Erdoğan and his visit to İznik, the site of the First Council of Nicaea, highlighted Turkey’s deep Christian heritage and the importance of interreligious dialogue. Turkey has made progress in recent years through property restitution, cultural-heritage restoration, and increased cooperation with minority communities. However, structural challenges remain, including the lack of legal personality for religious institutions, restrictions on clergy education, and administrative barriers affecting church properties. The long-closed Halki Seminary remains a key unresolved issue for the Orthodox world. The visit served as both a diplomatic engagement and a symbolic reminder of Turkey’s multi-religious identity. It also created an opportunity for renewed dialogue between Turkey, the Vatican, and minority groups on religious-freedom reforms. Overall, the Pope’s visit has the potential to become a catalyst for improving legal protections and societal acceptance of religious diversity in Turkey.

Legal Framework of Religious Freedom in Turkey

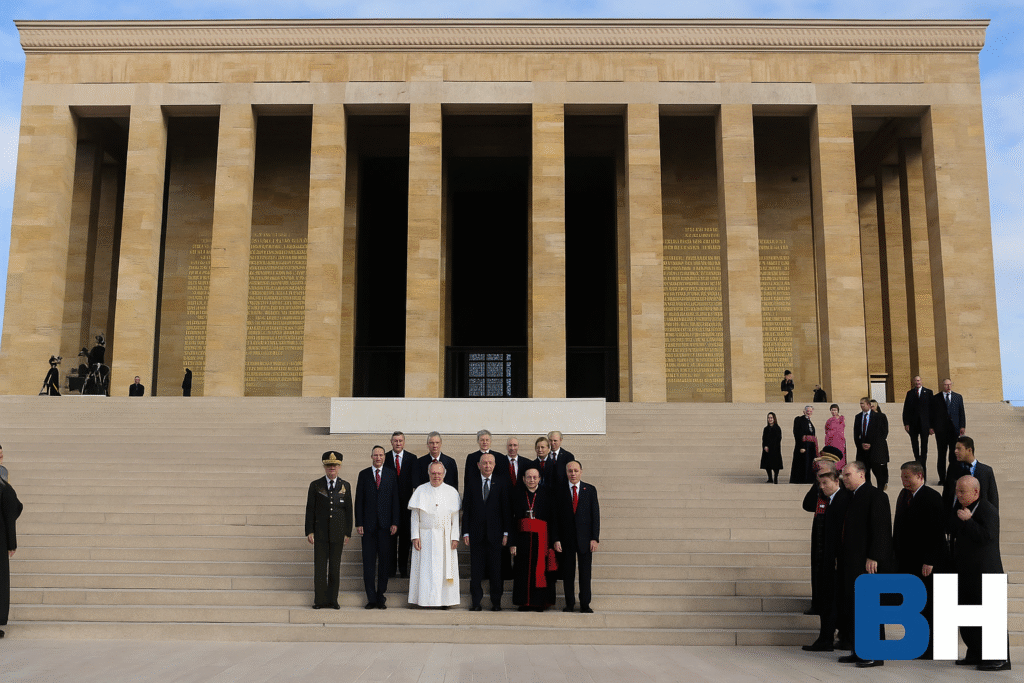

Pope Leo XIV’s November 2025 visit to Turkey – the first foreign visit of his papacy – marked an important diplomatic, religious, and symbolic moment for Turkey and the broader region. His meetings with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, his highly watched visit to Istanbul and İznik, and his remarks emphasizing peace, dialogue, and the historic Christian presence in Anatolia brought renewed attention to the state of religious freedom in Turkey.

The New York Times and other global media outlets framed the visit as a significant opportunity for re-engagement between Turkey and the Vatican at a time of heightened geopolitical tensions. Beyond symbolic gestures, however, the visit reopened deeper questions:

- What is the status of religious freedom in Turkey today?

- How do Christian and other minority communities exercise their rights?

- What progress has been achieved, and what structural challenges remain?

- How might this high-profile visit influence future reforms?

This article explores these issues through the lens of the papal visit, combining legal analysis with current developments and policy considerations. It also outlines how Bıçak Law Firm supports clients navigating the complex landscape of religious-freedom law, human-rights protections, and constitutional guarantees in Turkey.

Turkey’s Constitutional and Legal Foundation for Religious Freedom

Secularism and the Constitutional Framework

Turkey’s Constitution guarantees freedom of conscience, belief, and religious expression (Article 24) and equality before the law without discrimination (Article 10). Article 90 further establishes the supremacy of international human-rights treaties – such as the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) – over domestic law in cases of conflict.

However, Turkey’s model of secularism (“laiklik”) is unique. Unlike the American or French systems, it places religion under state supervision through strong bureaucratic structures and regulatory mechanisms. The Presidency of Religious Affairs (Diyanet), an institution funded by the state budget, has authority over Islamic religious services but not over other faiths.

This asymmetrical model can lead to practical challenges for non-Muslim communities seeking equal access to public resources, legal personality, and institutional representation.

Lausanne Treaty Minorities

Turkey officially recognizes only the communities enumerated in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne:

- Greek Orthodox Christians

- Armenian Apostolic Christians

- Jewish communities

Other longstanding groups – Syriac Orthodox, Chaldeans, Catholics, Protestants – are not formally recognized as minorities under Lausanne, which affects their institutional rights and administrative treatment. The absence of recognition does not mean these communities lack basic rights; they operate through associations, foundations (vakıf), or cultural initiatives. However, lack of collective legal personality complicates their operations, property ownership, community governance, and clerical training.

Christian Communities in Contemporary Turkey

Anatolia is historically one of the centers of global Christianity. The seven churches of Asia Minor, early councils including Nicaea (325 AD), and centuries-old monastic traditions form the religious heritage landscape. Yet from the 19th century onward, demographic shifts, conflict, political transformation, and migration dramatically reduced Christian populations. The communities that remain today are small but significant in culture, history, and diplomacy.

Current Community Dynamics

- Greek Orthodox Community: Led by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, headquartered in Istanbul, but significantly reduced in size.

- Armenian Apostolic Community: Maintains churches, schools, foundations, and a Patriarchate in Istanbul.

- Syriac Community: Active in Istanbul and southeastern provinces such as Mardin; known for its ancient monastic centers.

- Catholic Communities: Latin, Armenian, Chaldean, and Syrian Catholic groups maintain parishes in major cities.

- Protestant Communities: Composed of small, dispersed congregations, growing modestly with new converts and expatriates.

Despite demographic challenges, many communities report improved conditions in recent decades, including restoration of properties, increased visibility, and cooperation with local authorities. However, systemic legal issues remain unresolved.

The Pope’s 2025 Visit: Diplomatic, Cultural, and Religious Significance

The New York Times article highlighted the diplomatic sensitivity of the visit. Pope Leo XIV’s stop in Ankara and meeting with President Erdoğan took place amid complex global crises and regional instability. The Vatican’s emphasis on peace, dialogue, and coexistence aligned closely with Turkey’s messaging on regional leadership.

One of the most significant elements of the visit was the Pope’s travel to İznik to commemorate the 1700th anniversary of the First Council of Nicaea – a foundational event for Christian theology. Global media noted that this choice symbolically reconnected Turkey with its Christian heritage and underscored its importance to global Christianity. By visiting İznik, the Pope implicitly reminded the world that Turkey is not merely a majority-Muslim state but also a historic center of Christian civilization.

Papal Messages on Religious Freedom: Across his speeches, the Pope stressed:

- the historic and contemporary presence of Christians in Turkey

- the need to ensure respectful coexistence

- the importance of preserving religious heritage sites

- the role of the state in enabling religious communities to flourish

These themes resonated globally and domestically, and they placed religious-freedom issues under renewed scrutiny.

Progress and Positive Developments in Religious Freedom

The Pope’s visit itself is a form of progress. Steps such as:

- the President’s formal invitation

- protocol-level hospitality

- meetings with Christian and Muslim leaders

- joint messages promoting dialogue

signaled a willingness to maintain open communication between Turkey and Christian communities globally.

- Property Restitution and Cultural Preservation: Over the past decade, Turkey has returned numerous confiscated minority-community properties, including churches, schools, and cemeteries. Restoration projects – some with state support – have taken place in Istanbul, Hatay, Mardin, and other regions.

- Freedom of Worship and Community Activity: In major cities such as Istanbul, congregations worship freely and maintain public religious ceremonies. Many communities report constructive cooperation with provincial authorities on local issues.

- Increased Visibility of Christian Heritage: Recent archaeological and cultural projects have highlighted Turkey’s Christian past, including restoration of historic churches and reopening of heritage sites to tourism. These efforts contribute to social recognition and international goodwill.

Ongoing Legal and Institutional Challenges

Despite progress, systemic issues continue to affect religious freedom.

- Lack of Legal Personality for Religious Communities: Churches cannot register as “religious institutions.” Instead, they rely on:

- foundations (vakıf)

- cultural associations

- informal councils or community boards

This structure complicates representation, governance, property acquisition, and long-term planning.

- Clergy Education and the Halki Seminary Issue: The closure of the Halki Seminary in 1971 remains a central concern for the Ecumenical Patriarchate and the global Orthodox world. The institutional inability to train clergy in Turkey affects leadership continuity and is often cited in international human-rights reports.

The Pope’s visit brought intense attention to the issue, raising hopes for future progress.

- Property Rights and Administrative Barriers: Although progress has been significant, some foundations still face:

- lengthy litigation over historical properties

- administrative restrictions on construction or restoration of churches

- inconsistent implementation of regulations across provinces

- Societal Perceptions and Security Concerns: Isolated incidents of hostility, misinformation, or vandalism – while not systematic – contribute to a sense of vulnerability among religious minorities.

Efforts to foster tolerance, intercultural education, and social inclusion remain essential.

International Law and Turkey’s Obligations

Turkey is bound by the ECHR and subject to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which has ruled on cases involving:

- religious foundations

- minority education

- property rights

- freedom of worship

ECtHR jurisprudence consistently emphasizes:

- neutrality of the state

- proportionality of restrictions

- protection of collective religious practice

As a party to key UN treaties, Turkey is committed to protecting religious freedom, cultural rights, and nondiscrimination.

Religious freedom intersects with Turkey’s relations with:

- the EU

- the Council of Europe

- the Vatican

- the United States (Reports on International Religious Freedom)

Papal visits often influence the tone of these relationships.

How the Pope’s Visit Influences Future Prospects

The visit heightened global attention to religious pluralism in Turkey. Constructive engagement may lead to:

- more frequent dialogue

- confidence-building measures

- administrative improvements in local practices

Both domestic and international actors view the reopening of the Halki Seminary as attainable, particularly if framed as:

- a cultural heritage initiative

- a gesture of goodwill

- a contribution to Turkey’s international image

Christian heritage sites are valuable cultural and economic assets. The Pope’s visit highlighted the potential for heritage-centric tourism and intercultural understanding.

The visit also functions as an educational moment within Turkey, reinforcing messages of:

- tolerance

- coexistence

- respect for diversity

Policy Recommendations for Strengthening Religious Freedom

Legal Reforms

- Introduce a legal framework allowing religious communities to register as religious institutions.

- Recognize additional communities beyond Lausanne categories.

- Streamline administrative processes for building, restoring, or managing houses of worship.

Institutional and Educational Improvements

- Reopen seminaries and update regulations governing religious education.

- Promote intercultural awareness programs in schools.

Enhanced Protection of Religious Heritage

- Provide consistent protection for churches, monasteries, and cemeteries.

- Partner with UNESCO and international organizations for conservation projects.

Strengthening Dialogue Mechanisms

- Establish regular consultation platforms between the state and minority communities.

- Support diplomatic cooperation with the Vatican and international civil-society organizations.

Conclusion

Pope Leo XIV’s visit to Turkey in 2025 was more than a symbolic diplomatic ritual. It illuminated the historic depth of Christianity in Turkey, celebrated the possibility of interreligious harmony, and renewed attention to the condition of religious freedom in the country. Turkey has made notable strides in recent decades, especially through property restitution, greater cultural openness, and improved dialogue.

However, structural issues – legal personality, clerical education, and administrative burdens – persist. Addressing these challenges would not only strengthen the rights of minority communities but also enhance Turkey’s international standing as a country committed to pluralism and democratic values. The visit has opened a window of opportunity. The next steps will determine whether this moment becomes a meaningful turning point.

How Bıçak Law Firm Assists in Matters of Religious Freedom and Human Rights? At Bıçak Law Firm, we provide comprehensive legal services in:

- Human rights and constitutional litigation

- Freedom of religion, conscience, and belief cases

- Representation before Turkish courts and international bodies

- Advising religious foundations, associations, and minority institutions

- Property rights, heritage protection, and administrative disputes

- Compliance with international human-rights standards

- Legal due diligence for heritage projects and cultural institutions

With decades of experience in public law, constitutional law, international human rights, and comparative legal systems, our team is uniquely positioned to support both individual clients and institutions seeking to protect religious freedoms and cultural rights in Turkey.

English

English Türkçe

Türkçe Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch

Comments

No comments yet.