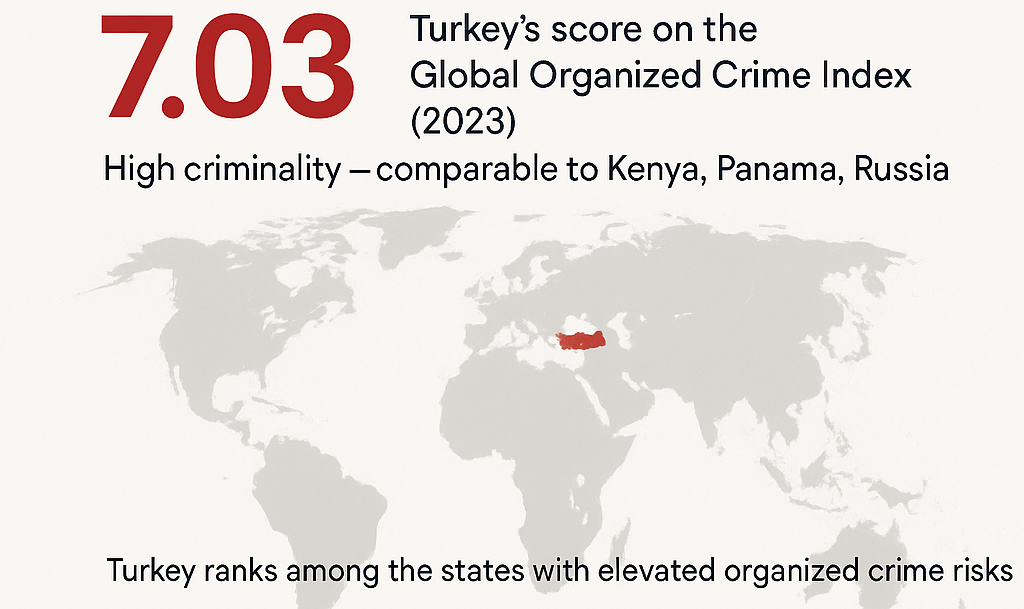

Organized crime has profoundly shaped the Turkish state, influencing politics, security, and the economy from the Ottoman era to the present day. The legacy of the Susurluk scandal, the prominence of mafia bosses like Alaattin Çakıcı and Sedat Peker, and the continued power of clans such as the Sarallar, Söylemezler, and Daltonlar illustrate how criminal networks have operated not outside but often within state structures. According to the Global Organized Crime Index (2023), Turkey scores 7.03, placing it among countries with elevated levels of criminality. Key drivers include drug trafficking, human smuggling, financial crime, and state-embedded actors, while resilience remains weak due to judicial politicization, corruption, and selective enforcement – factors reinforced by Turkey’s position on the FATF grey list. Organized crime in Turkey is therefore a structural force: eroding the rule of law, distorting markets, creating parallel power structures, and weakening democratic institutions. For international businesses and investors, these realities present direct compliance, due diligence, and reputational risks, making robust legal guidance essential.

How Organized Crime Shapes the Turkish State

Turkish Organized crime is not simply a question of illegal markets or criminal gangs operating in isolation. In Turkey, it has historically intersected with politics, economics, and state institutions, creating a unique and complex phenomenon that has influenced the very fabric of governance. Far from being limited to underworld activity, organized crime has at times operated in parallel with, or even in partnership with, elements of the state itself.

Turkey’s geographic position – straddling Europe, Asia, and the Middle East – has made it both a transit hub and a destination for illicit markets. From narcotics and arms trafficking to human smuggling and money laundering, the country occupies a central role in regional and global criminal networks. This strategic location, combined with historical traditions of patronage and informal power structures, has enabled organized crime to exert influence far beyond conventional law-and-order concerns.

The effects are far-reaching. Organized crime not only fuels corruption and undermines the rule of law but also distorts the economy, deters foreign investment, and weakens democratic institutions. It erodes public trust in justice and governance, blurring the line between legitimate and illegitimate power.

Against this backdrop, it is essential to ask: How has organized crime shaped the Turkish state? By exploring historical milestones, contemporary dynamics, international assessments such as the Global Organized Crime Index, and emblematic case studies, we can better understand the depth of the challenge and the risks it poses for businesses, policymakers, and citizens alike.

For international investors, diplomats, and legal professionals, this issue is not only of academic or political interest. It directly affects compliance risks, due diligence standards, and the overall stability of the legal and business environment in Turkey.

Historical Background

The phenomenon of organized crime in Turkey cannot be understood without considering the country’s long history of informal networks, clandestine economies, and state-crime overlaps. From the Ottoman era to the present, these structures have not only survived but in many respects adapted and flourished, embedding themselves into Turkey’s political and economic order.

Ottoman Legacy: Informal Networks and Contraband

During the late Ottoman period, the empire’s vast geography and weak central control in its peripheries created fertile ground for smuggling and contraband markets. Salt, tobacco, and arms were frequently traded outside official channels, often with the tacit tolerance of local officials. Patronage systems, clan loyalties, and the use of non-state intermediaries for taxation and security contributed to the normalization of illicit economies. These practices laid the groundwork for later criminal networks that would operate in similar grey zones of legality and authority.

Early Republican Period (1923–1980s): State-Building and Nationalist Networks

With the foundation of the Republic in 1923, the new state sought to centralize authority and suppress non-state actors. However, informal networks remained influential. Political patronage and clandestine economic activities – especially smuggling along Turkey’s borders – continued to thrive. By the 1950s and 1960s, illicit trade in tobacco, alcohol, and fuel had become part of the economic life of border regions.

The Cold War era intensified these dynamics. Turkey’s strategic position as a NATO member placed it at the crossroads of ideological and geopolitical struggles. Paramilitary organizations and ultranationalist groups, some with state backing, emerged not only as political actors but also as participants in organized criminal activity. These groups engaged in extortion, arms trafficking, and illicit financing to sustain their operations. The line between ideological struggle and profit-driven crime often blurred.

The 1970s–1980s: Seeds of the “Deep State”

Political instability, street violence, and military interventions created an environment where covert alliances between elements of the security services and organized criminal groups thrived. Criminal networks offered the state extra-legal tools to combat perceived internal and external threats. In return, they were granted protection, impunity, and access to lucrative illicit markets.

By the 1980s, following the 1980 military coup, Turkey experienced rapid economic liberalization. While formal markets opened to global capital, illicit markets also expanded – particularly in drug trafficking, gambling, and human smuggling. This period set the stage for the scandals of the 1990s, when the intimate ties between organized crime and the state would be dramatically exposed to public view.

The Modern Turkish State and Organized Crime

Organized crime in Turkey entered a highly visible phase in the late 20th century. Unlike earlier periods, when illicit activities were largely confined to border regions or ideological networks, the 1990s revealed the extent to which criminal actors had penetrated the political system and state institutions. This era introduced the concept of the “deep state” (derin devlet) into public discourse- a shadowy network of politicians, security officials, and criminal figures alleged to work in concert for both profit and political ends.

The Susurluk Scandal: A Turning Point (1996)

The defining moment of the 1990s came in 1996 with the Susurluk car crash. The accident, involving a senior police chief, a sitting member of parliament, and the ultranationalist crime boss Abdullah Çatlı, exposed to the public the close ties between state authorities and organized criminal figures. The revelations that followed confirmed that criminal networks were used by elements of the state for counterinsurgency, political intimidation, and illicit funding through drug trafficking and extortion.

Although the scandal shocked the public and led to parliamentary inquiries, accountability was minimal, and systemic reforms were never fully realized.

Security Institutions and Criminal Networks

The 1990s also marked an era when segments of the police, intelligence services, and paramilitary units were found to be working in tandem with organized crime groups. Justified under the guise of counterterrorism, these collaborations gave mafia groups immunity from prosecution. In some cases, criminal figures acted as unofficial enforcers of state policy.

Economic Dimensions of Crime – State Interactions

Organized crime expanded into lucrative sectors:

- Drug trafficking: Turkey remained a critical hub for heroin from Afghanistan to Europe.

- Smuggling: Fuel, cigarettes, and alcohol smuggling thrived with official protection.

- Construction, tourism, and gambling: Illicit capital was laundered through legal businesses.

From 2000 to 2010: Shifting Alliances

The early 2000s brought significant political changes. The rise of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2002 initially appeared to weaken some “deep state” networks. High-profile trials, such as Ergenekon and Balyoz, targeted military and nationalist figures accused of plotting against the government, some of whom had past links to organized crime.

Yet, while some networks were dismantled, new ones emerged. Criminal groups adapted by aligning themselves with the new political order. In this period, figures such as Alaattin Çakıcı continued to symbolize the enduring influence of mafia bosses in politics and business, even from behind prison walls.

The 2010s: Consolidation and New Patterns

By the 2010s, organized crime had evolved alongside political centralization. Several dynamics stood out:

- Drug markets diversified: Turkey became a key player not only in heroin transit but also in the synthetic drug trade.

- International reach: Turkish groups extended their networks into Europe, the Caucasus, and the Middle East.

- Politicization of justice: Selective prosecutions of crime figures suggested that criminal networks were not being dismantled uniformly but were instead managed depending on political loyalties.

- Çakıcı’s symbolic role: Even while imprisoned, Çakıcı maintained political influence, particularly through ultranationalist networks. His eventual release in 2020 under a controversial amnesty law – reportedly supported by the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) – was widely criticized as evidence of political favoritism in criminal justice.

2020–2025: Contemporary Exposure

The past five years have brought new revelations and challenges:

- Sedat Peker’s Video Revelations (2021): Once a powerful mafia boss with alleged political ties, Peker released a series of online videos from abroad accusing senior officials of corruption, drug trafficking, and mafia-state collusion. His disclosures reignited national and international debates about organized crime’s reach into Turkish politics.

- Ongoing EU and US Concerns: International reports, including those from the European Commission and US State Department, have continued to highlight Turkey’s vulnerability to organized crime, especially in money laundering, human trafficking, and narcotics trade.

- Mafia-State Symbolism: Figures like Çakıcı (amnestied in 2020) and Peker illustrate the dual nature of organized crime in Turkey: sometimes suppressed, sometimes tolerated, and sometimes integrated into political struggles.

Lasting Legacy of 1990–2025

The period from the Susurluk scandal to the Peker revelations shows that organized crime in Turkey is not episodic but structural. Networks adapt to political shifts, embedding themselves into different regimes. Whether through counterinsurgency alliances in the 1990s, selective prosecutions in the 2000s, or symbolic amnesties and whistleblowing in the 2020s, the fundamental pattern remains: organized crime has shaped and continues to shape the contours of the Turkish state.

The Global Organized Crime Index and Turkey’s Position

Understanding the scale of organized crime in Turkey requires not only historical and political analysis but also comparative measurement. One of the most authoritative benchmarks is the Global Organized Crime Index (OCIndex), developed by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC). Covering all 193 UN member states, the Index evaluates two key dimensions:

- Criminality: the scope and intensity of illicit markets such as drug trafficking, human smuggling, financial crime, and state-embedded criminality.

- Resilience: the strength of a state’s institutions and policies in resisting, prosecuting, and dismantling organized crime.

Turkey’s Score and Ranking

According to the 2023 Global Organized Crime Index, Turkey scores 7.03, placing it among the countries with high levels of criminality and relatively weak resilience. This score situates Turkey in a concerning bracket – comparable to Kenya (7.02), Panama (6.98), and Russia (6.87).

The Index highlights Turkey as a regional hub for multiple illicit markets:

- Drug trafficking: particularly heroin routes from Afghanistan through Turkey to Europe.

- Human smuggling and trafficking: leveraging Turkey’s geographic position as a gateway between Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.

- Fuel and arms smuggling: exacerbated by regional conflicts in Syria and Iraq.

- Financial crimes and money laundering: exploiting the gaps in regulatory enforcement and the politicization of oversight bodies.

State-Embedded Actors and Criminal Networks

The OCIndex emphasizes the role of state-embedded actors – political figures, bureaucrats, and security officials – who either directly participate in, protect, or benefit from organized crime. In Turkey, the overlap between state institutions and illicit networks, dating back to Susurluk, continues to undermine resilience.

While Turkey has extensive laws on organized crime and money laundering, enforcement remains uneven and politicized. Certain groups are targeted harshly, while others benefit from impunity due to political connections. This selective application of the law weakens deterrence and reinforces perceptions of corruption.

Weak Resilience Despite Legal Frameworks

Despite being a NATO member, a candidate country for EU membership, and a signatory to international conventions such as the Palermo Convention, Turkey’s resilience score remains low. This is attributed to:

- Judicial politicization: lack of independence undermines impartial prosecution of crime.

- Corruption: from local police to high-level officials.

- Civil society restrictions: NGOs and investigative journalists who expose crime networks face harassment and criminalization.

- Financial oversight gaps: MASAK (Financial Crimes Investigation Board) exists on paper but is criticized for selective investigations.

Implications for Turkey and Beyond

The Index data confirm what domestic scandals and whistleblowers have long revealed: organized crime in Turkey is not a marginal problem but a structural challenge. It weakens governance, distorts the economy, and erodes trust in the rule of law.

For international businesses and investors, Turkey’s ranking in the OCIndex highlights the importance of:

- Conducting rigorous due diligence before engaging in partnerships or acquisitions.

- Implementing anti-money laundering (AML) compliance mechanisms.

- Understanding the political economy risks that arise from the blurred lines between state and criminal actors.

Legal and Institutional Framework

While Turkey’s ranking in the Global Organized Crime Index highlights the scale of the challenge, it is equally important to examine the legal and institutional framework through which the state seeks to combat organized crime. On paper, Turkey has developed comprehensive legislation and established multiple oversight bodies. Yet, in practice, enforcement is frequently undermined by politicization, corruption, and selective application of the law.

Criminal Law Provisions

The Turkish Penal Code (TCK) contains detailed provisions addressing organized crime:

- Article 220 criminalizes the establishment, leadership, or membership of an organization formed with the intent to commit crimes. It also penalizes assistance to such organizations.

- Articles 314–316 cover armed organizations and attempts against the constitutional order, which often intersect with organized crime in cases involving paramilitary or politically motivated groups.

- Enhanced penalties apply when crimes are committed within the framework of an organized structure, reflecting the recognition that such offenses pose a greater threat to public order and governance.

Anti-Money Laundering Regime (MASAK)

The Financial Crimes Investigation Board (MASAK) is Turkey’s primary body tasked with combating money laundering and the financing of terrorism. Established under the Law on Prevention of Laundering Proceeds of Crime (1996, amended 2006), MASAK has the mandate to:

- Monitor suspicious financial transactions.

- Enforce compliance obligations on banks, financial institutions, and designated non-financial businesses.

- Cooperate with international financial intelligence units (FIUs).

However, MASAK has been criticized for selective enforcement. Investigations often target political opponents or adversarial networks, while groups aligned with the ruling establishment may enjoy relative impunity. This undermines confidence in the impartiality of the regime.

Institutional Actors

- Police and Gendarmerie: frontline agencies in detecting and suppressing organized crime. Their effectiveness is often hampered by corruption, limited resources, or political interference.

- Judiciary: tasked with prosecuting organized crime cases. However, international observers, including the European Commission, repeatedly stress the lack of judicial independence as a key weakness.

- Prosecutor’s Offices: although specialized organized crime bureaus exist, prosecutions can be inconsistent, particularly in high-profile cases involving politically connected individuals.

International Legal Commitments

Turkey is a party to several international frameworks:

- UN Palermo Convention (2000) on Transnational Organized Crime.

- Council of Europe GRECO mechanism on anti-corruption monitoring.

- Financial Action Task Force (FATF) standards on anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing.

Despite these commitments, Turkey has faced international scrutiny. In 2021, FATF placed Turkey on its “grey list” for deficiencies in AML/CFT implementation, noting risks related to high-risk sectors and politically exposed persons (PEPs). This designation signals to the global financial community that transactions in and through Turkey require enhanced scrutiny.

Enforcement Challenges

The gap between law and practice remains striking:

- Selective justice: Prosecutions often reflect political priorities rather than impartial law enforcement.

- Corruption and impunity: State-embedded actors can shield criminal groups from accountability.

- Institutional weakness: Civil society and investigative journalism, key watchdogs in countering organized crime, face legal and political restrictions.

- International pressure vs. domestic realities: While Turkey enacts reforms in response to EU or FATF monitoring, their implementation is inconsistent.

In summary, Turkey has developed a strong legal arsenal and participates in major international conventions, but its low resilience score in the OCIndex reflects the enforcement deficit. Laws exist, but the rule of law is weakened when justice is selective, oversight bodies are politicized, and state-embedded actors continue to operate with impunity.

Contemporary Dynamics

While Turkey’s history with organized crime stretches back decades, the 2000–2025 period has witnessed the transformation of criminal networks into actors with transnational reach and political resonance. The globalization of illicit markets, Turkey’s strategic geography, and domestic political developments have combined to place organized crime at the center of contemporary debates about governance and state integrity.

Turkey as a Transnational Hub

Turkey remains one of the most important corridors for international criminal markets:

- Drug trafficking: Heroin routes from Afghanistan continue to pass through Turkey en route to Europe. In recent years, synthetic drugs (especially Captagon and methamphetamines) have also featured in Turkish seizures, linking Turkey to Middle Eastern and Asian networks.

- Human smuggling and trafficking: Political instability in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan has turned Turkey into both a staging ground and transit country for migrant smuggling toward Europe. Criminal groups profit heavily from these flows.

- Arms and fuel smuggling: Conflicts in Syria and Iraq have sustained lucrative illicit trade in weapons and fuel, with Turkish border regions playing a critical role.

- Financial crime and laundering: Turkey has emerged as a significant hub for illicit financial flows, with its banking and real estate sectors identified by FATF and EU reports as vulnerable to abuse.

Political Dimensions

Organized crime in Turkey is not merely an economic phenomenon – it carries clear political implications:

- State–mafia relations: Criminal bosses often maintain or claim ties to politicians, seeking protection or legitimacy.

- Selective justice: As seen with the 2020 amnesty that freed Alaattin Çakıcı, the state’s treatment of high-profile crime figures is perceived to depend on political loyalty rather than purely legal criteria.

- Instrumentalization of criminal networks: Some organized crime figures are alleged to have been used for political intimidation, campaign financing, or extra-legal enforcement, echoing the patterns revealed by Susurluk in the 1990s.

The Sedat Peker Revelations

Perhaps the most vivid example of contemporary dynamics came in 2021, when mafia boss Sedat Peker, in self-imposed exile, released a series of online videos accusing senior government officials of corruption, drug trafficking, and mafia–state collusion. These disclosures, viewed millions of times, reignited national and international debate about the depth of organized crime’s influence.

Although Turkish authorities dismissed his claims, Peker’s revelations resonated with the public because they aligned with long-standing suspicions about state–crime linkages. The scandal also attracted global attention, with foreign media and policy institutions citing it as evidence of systemic corruption.

Organized Crime in Public Discourse

Organized crime has also become a cultural and media phenomenon in Turkey. Popular TV dramas such as Kurtlar Vadisi (“Valley of the Wolves”) dramatize the intersection of mafia, politics, and state security, often blurring the line between fiction and reality. Public fascination with crime bosses like Çakıcı and Peker underscores how organized crime figures are not only feared but sometimes admired, reflecting both cynicism and distrust toward official institutions.

International Pressure

The European Commission’s annual progress reports and the U.S. State Department’s narcotics and human trafficking assessments consistently highlight Turkey’s role as a hub for illicit markets. These reports emphasize the country’s vulnerabilities in money laundering, judicial independence, and enforcement consistency.

In 2021, Turkey was placed on the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) grey list, signaling international concern about its deficiencies in tackling money laundering and terrorism financing. Although Turkish authorities have since pledged reforms, the listing damaged Turkey’s financial reputation and raised compliance costs for international business.

In short, contemporary dynamics confirm that organized crime in Turkey is both global and domestic: it thrives on international trafficking routes while shaping political life at home. The Peker revelations, Çakıcı’s political rehabilitation, and recurring EU/FATF concerns illustrate that organized crime is not a peripheral issue but a structural force with economic, political, and cultural implications.

Case Studies

Case studies provide a concrete lens through which to understand how organized crime has shaped the Turkish state. From emblematic scandals to notorious crime bosses and powerful clans, each example reveals a different aspect of the state–crime nexus.

The Susurluk Scandal (1996)

The Susurluk car crash remains the single most iconic symbol of Turkey’s deep state. The accident involved:

- Abdullah Çatlı (an ultranationalist militant and wanted criminal),

- Hüseyin Kocadağ (a senior police chief), and

- Sedat Bucak (a Kurdish parliamentarian leading a state-backed paramilitary “village guard” clan).

The crash exposed how state officials, mafia figures, and paramilitary networks collaborated in counterinsurgency, political intimidation, and illicit trade. Parliamentary inquiries and media coverage revealed widespread corruption, but accountability was minimal. Susurluk established in public consciousness the idea that organized crime was deeply embedded in the state apparatus, not merely operating outside it.

Alaattin Çakıcı: The Political Godfather

Alaattin Çakıcı, one of Turkey’s most notorious mafia bosses, symbolizes the enduring influence of organized crime on politics. Convicted for ordering assassinations and involved in extortion and smuggling, Çakıcı maintained strong ties with the ultranationalist movement (MHP).

Even while imprisoned, his statements carried political weight. His release in 2020 under a controversial amnesty law—strongly backed by the MHP—was seen as a political gesture rather than a purely legal decision. Today, Çakıcı remains a living reminder of how mafia figures can act as both criminal leaders and political actors.

Sedat Peker: The Digital Whistleblower

Once a loyal ally of segments of the political elite, mafia boss Sedat Peker fled Turkey and in 2021 began releasing explosive video statements on YouTube. His accusations against government officials included:

- Corruption in state tenders,

- Drug trafficking routes allegedly involving political elites,

- Use of mafia networks for intimidation and extra-legal operations.

Peker’s revelations shocked the public and attracted global attention, illustrating how criminal insiders can disrupt political legitimacy when alliances shift. While authorities dismissed his claims, their resonance reflected deep public mistrust in the independence of institutions.

Selahattin Yılmaz

Selahattin Yılmaz, a prominent crime boss known for extortion and violent enforcement operations, represents another face of the mafia–state dynamic. His networks operated largely in major Turkish cities, often intersecting with both political and business elites. Yılmaz’s rise demonstrated how organized crime figures leveraged urban influence and intimidation to control markets ranging from construction to nightlife.

The Daltonlar Gang

The “Daltonlar” (named after the comic-book outlaws) emerged as a powerful organized crime group in the 1990s and 2000s, notorious for armed clashes, extortion, and trafficking. Known for their flamboyant violence, they became symbolic of street-level mafia warfare spilling into public life. While not as politically connected as Çakıcı or Peker, the Daltonlar highlighted how urban gangs escalated into organized structures, often tolerated or ignored until their activities became too visible.

The Söylemezler Gang

The Söylemezler were another prominent clan involved in armed organized crime in the 1990s. Their conflict with the Yüksel Clan led to bloody confrontations in Ankara, culminating in the infamous “Bar Shootout” case. Investigations revealed their ties with elements of the police and military. The Söylemezler saga showed how clan-based mafias infiltrated capital city politics and security structures, reinforcing the Susurluk narrative of a blurred line between crime and state.

The Sarallar Clan

The Sarallar, based primarily in Istanbul, represent one of the most enduring and powerful crime families in Turkey. Their operations have spanned real estate, construction, and entertainment sectors, often as fronts for money laundering and extortion. In recent years, large police operations against the Sarallar exposed their involvement in racketeering, intimidation, and fraud, implicating dozens of associates. Despite high-profile raids, the clan’s resilience demonstrates how deeply entrenched mafia families can become in urban economies and politics.

Lessons from the Case Studies

Taken together, these cases illustrate:

- Continuity: From Susurluk in 1996 to Peker’s revelations in the 2020s, the intertwining of crime and state remains a constant feature.

- Diversity of actors: From nationalist “godfathers” like Çakıcı, to whistleblowers like Peker, to clan-based groups like the Sarallar and Söylemezler, organized crime in Turkey has multiple faces.

- Structural influence: These groups are not merely criminal; they shape politics, business, and public discourse, revealing systemic vulnerabilities in governance and law enforcement.

How Organized Crime Shapes the State

Organized crime in Turkey is not merely a law enforcement issue; it is a structural force that influences politics, governance, and society at large. From the Susurluk scandal in the 1990s to Sedat Peker’s digital revelations in the 2020s, the recurring theme is that organized crime has operated not outside the state, but often through and alongside it. This has reshaped how the Turkish state functions in several key ways.

Erosion of the Rule of Law

The entanglement of mafia figures with politicians and security officials undermines the principle of equality before the law. When figures such as Alaattin Çakıcı receive amnesty due to political alliances, while rival groups face harsh prosecutions, it sends a clear message that justice is selective. This erodes public confidence in courts and law enforcement, weakening the foundations of the legal system.

Parallel Power Structures

Organized crime creates alternative centers of authority. Crime bosses, clans, and smuggling networks provide protection, economic opportunity, and even dispute resolution in areas where the state is absent or distrusted. In some cases, they are instrumentalized by state actors themselves, further legitimizing their power. These parallel structures dilute the state’s monopoly on violence and justice.

Distortion of the Economy

Illicit capital distorts competition by infiltrating legitimate markets such as construction, tourism, real estate, and entertainment. Money laundering through these sectors disadvantages honest businesses and deters foreign investment. At the macro level, Turkey’s placement on the FATF grey list underscores how organized crime undermines the credibility of its financial system in the eyes of international investors and regulators.

Weakening of Democratic Institutions

Organized crime undermines democracy by entrenching clientelism and patronage. Politicians benefit from the funds and coercive power of mafia actors, while criminal groups gain protection from prosecution. This symbiotic relationship reduces transparency, accountability, and electoral fairness. Revelations by figures like Sedat Peker also show how criminal actors can shape public discourse, bypassing formal institutions and amplifying cynicism toward democratic processes.

Cultural and Social Impacts

Organized crime figures in Turkey are not only feared but sometimes admired, becoming symbols in popular culture. Media portrayals and public fascination with figures such as Çakıcı and Peker reflect both disillusionment with official institutions and a glamorization of alternative power. This normalization of mafia figures contributes to a culture of impunity, where criminality and politics are seen as inseparable.

In sum, organized crime shapes the Turkish state by hollowing out the rule of law, creating parallel structures of power, distorting economic life, and undermining democratic accountability. It is not a peripheral challenge but a central factor in the state’s evolution.

Law Firm’s Perspective

For policymakers, journalists, or academics, the persistence of organized crime in Turkey may be a subject of political or sociological concern. For businesses, investors, and individuals, however, it is a matter of direct risk management. The realities described in the preceding chapters – state-mafia linkages, selective justice, systemic corruption, and financial vulnerabilities – translate into concrete risks that can jeopardize investments, transactions, and reputational integrity.

Risks for International Actors

- Compliance risks: International businesses operating in Turkey must comply not only with Turkish law but also with extraterritorial regimes such as EU anti-money laundering directives, US OFAC sanctions, and global corporate governance standards. The blurred line between licit and illicit capital in Turkey makes compliance a constant challenge.

- Due diligence obstacles: When organized crime infiltrates sectors like construction, real estate, or logistics, investors face difficulty distinguishing legitimate opportunities from criminally tainted enterprises.

- Asset exposure: Foreign individuals and companies may unwittingly enter into transactions involving assets tied to criminal networks, exposing them to legal action or sanctions abroad.

- Reputational harm: Associations – whether direct or indirect – with criminally tainted actors in Turkey can severely damage a company’s global credibility.

Bıçak’s Expertise

At Bıçak Law Firm, we recognize that navigating Turkey’s business and legal landscape requires more than knowledge of statutes – it requires a practical understanding of how organized crime shapes the state. Our services are designed to mitigate these risks:

- Asset Tracing and Recovery: Locating and securing assets misappropriated through fraud, corruption, or criminal infiltration.

- Compliance and Due Diligence: Advising international investors on AML/CFT obligations, conducting background checks, and mapping risks of corruption or criminal exposure in transactions.

- White-Collar Crime Defense: Representing clients facing allegations or investigations, ensuring fair trial rights, and challenging politically motivated prosecutions.

- Sanctions and International Law: Advising on compliance with international sanctions regimes, particularly where Turkish transactions intersect with US, EU, or UN restrictions.

- Litigation and Arbitration: Offering representation in disputes involving allegations of fraud, corruption, or organized crime-related breaches of contract.

Why Bıçak?

Our firm is uniquely positioned because:

- We combine academic depth with practical courtroom expertise.

- We maintain international partnerships through networks such as ILF (International Law Firms) and ABAL (Across Borders Alliance of Lawyers).

- We bring a comparative perspective, drawing on global best practices in asset recovery, compliance, and anti-corruption.

- We offer confidential, reliable, and strategic advice to embassies, multinational corporations, and private individuals operating in Turkey.

In essence, Bıçak Law Firm bridges the gap between theory and practice: we analyze how organized crime shapes the Turkish state, and we help our clients anticipate, mitigate, and navigate the legal and commercial risks that result.

Conclusion

Organized crime in Turkey is not an isolated criminal phenomenon – it is a structural force that has influenced the state for decades. From the Susurluk scandal of the 1990s, which exposed the deep ties between security institutions and mafia figures, to the amnesty of Alaattin Çakıcı and the revelations of Sedat Peker in the 2020s, one reality has remained constant: organized crime has been both a beneficiary of, and a contributor to, the political order.

The Global Organized Crime Index (2023) confirms what history and case studies already suggest: Turkey’s high criminality score (7.03) reflects entrenched vulnerabilities in governance, law enforcement, and financial regulation. Despite having a comprehensive legal framework and international obligations, resilience remains weak due to selective justice, corruption, and politicization of institutions.

The consequences are profound. Organized crime erodes the rule of law, creates parallel power structures, distorts the economy, and weakens democracy. It also complicates the environment for legitimate businesses, foreign investors, and international partners, who must navigate risks that extend far beyond ordinary commercial challenges.

At Bıçak Law Firm, we believe that understanding these dynamics is not only an academic exercise but a practical necessity. For embassies, multinational corporations, and private investors, the ability to operate safely and effectively in Turkey depends on recognizing how organized crime shapes the state – and taking proactive measures to mitigate its risks. Through services in compliance, due diligence, asset tracing, litigation, and sanctions advice, our firm stands ready to support clients in navigating this complex landscape.

Ultimately, Turkey’s challenge is to strengthen its resilience – to ensure that the rule of law, transparency, and accountability prevail over illicit networks. Until then, businesses and individuals engaging with Turkey must remain vigilant, well-advised, and strategically prepared.

English

English Türkçe

Türkçe Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch

Comments

No comments yet.